Over four years ago, Michelle Obama took to Twitter to post a simple picture that would shake the world. It's instantly recognizable: a plain photo of her standing in the White House, holding up a white piece of paper with "#BringBackOurGirls" written on it in ink.

The hashtag was part of a social media campaign to bring attention to the 276 Nigerian girls who were kidnapped from their Chibok school by Boko Haram and taken to the Sambisa Forest.

A few years later, following public outcry, the government was able to negotiate the release of 82 girls. (Other girls were able to escape or have been freed, but some of the Chibok girls are still with Boko Haram.)

"People were shocked and outraged by the kidnapping at the time," writer and producer Karen Edwards told ELLE.com, "but when they disappeared and the Nigerian Government was offering little or no new information, the news story moved on.

"It was my experience that when you mention the Chibok Girls and the BringBackOurGirl campaign, people were quick to remember. They were instantly curious about what had happened to them."

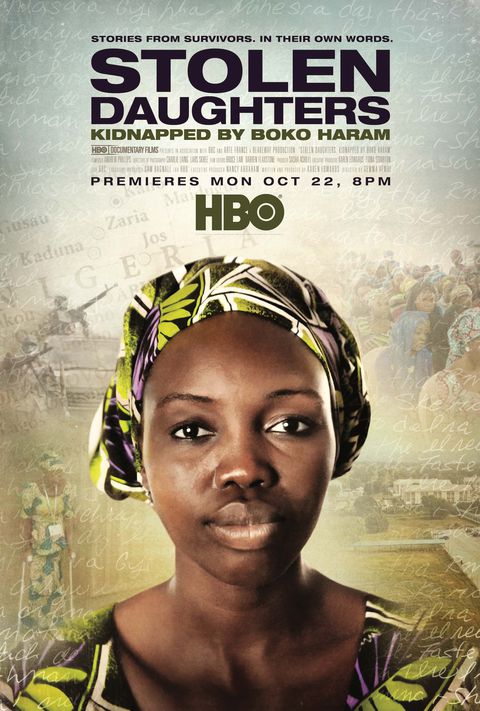

Their stories are now being told in the new HBO documentary "Stolen Daughters: Kidnapped by Boko Haram", which premieres on October 22.

Filmmakers were given exclusive access to the secret government safe house where the girls stayed after their release, but the girls are instructed, on film, not to share details of what happened in the forest, for fear they will be retargeted by the terrorist group and the other girls won't be released.

Through confidential diaries given to the filmmakers, and stories from the "Forgotten Girls" - others who have also escaped the terrorist group - the documentary gives insight into what happens to those taken by Boko Haram - and the future that lies ahead for those that escape.

Producer Sasha Achilli told ELLE.com that, during her interviews, many girls had a difficult time talking openly about the violence they experienced and often attributed events to a third person rather than speaking directly about themselves.

"In terms of personally hearing the stories of these girls, it is deeply sad," she said. "You also feel so powerless at times to be able to make a difference...they are victims of circumstance, and the only thing that is different between me and them, as a woman, is purely the fact that I was born in the West."

Throughout the film, we see the Chibok girls sitting in classrooms, at an amusement park, reuniting with their families, and getting ready to attend a government-funded program at the American University of Nigeria - all typical events you might see in a young girl's life. But the truth is always there; their lives are not typical, and nothing can erase the past.

One woman named Margret, 20, tells the filmmakers, "On the day I was released from captivity, I thought to myself, 'Am I really free from this suffering?' I thought to myself, 'I can't dwell on what happened to me.' I told myself that the past is like water. Once it is spilled, it's spilled forever."

The Chibok girls are only a small percentage of the women abducted by Boko Haram, and even their experience exists as an anomaly. Though the Chibok girls are being taken care of by the Nigerian government, the Forgotten Girls' lives are vastly different, with none of the same resources or access.

In one of the most heartwrenching moments of the documentary, 16-year-old Zahra, one of the Forgotten Girls, describes a time when she was forced to accompany Boko Haram to kidnap other girls.

She remembers one 14-year-old girl whose parents were killed during her abduction; she was then locked in a room and raped by about 10 men. She later died alone in that room. "She suffered a great deal of pain," Zahra recalls. "I will never forget her all my life." Zahra was able to escape from the group with two other girls, though she was the only one who made it back.

Although they've been through so much, girls who have escaped are still treated with trepidation by people in their communities, who fear they've been radicalized by Boko Haram and will become suicide bombers.

Achilli told ELLE.com that the filmmakers had to be very careful about interviewing the Forgotten Girls, since they did not want the girls' neighbors to know why they were being interviewed and then stigmatize them.

However, Edwards says they were careful to pick young women who did want to speak and share their stories. "These are not young women who are used to having a voice or being able to tell their stories," Edwards told ELLE.com.

"It's always hard working on a project where the characters have suffered such terrible trauma. You worry about the impact of asking questions. But it's not our place to deny them a voice by trying to double guess them or overprotect them to the point of silencing them."

She notes that, to protect the girls, they did change some of their names and will not be screening the documentary in Nigeria.

As the producers explain, many of the girls' experiences speak to broader issues: One Forgotten Girl named Habiba rescued two boys who escaped after being kidnapped to be child soldiers. And one Chibok girl named Hannatu lost part of her leg during a military airstrike while she was with Boko Haram.

They are complex issues, ones that seem to be missing from the international dialogue. When I ask the producers if they feel the public has forgotten about these girls, Edwards says, "I think it's inevitable that the fate of the Chibok girls could not remain at the forefront of peoples' minds after the news cycle moved on and the news stories stopped… Forgetting about them in that sense is not the same as the world not caring.

"What the world doesn't know is the scale of the problem and the thousands of other girls who are kidnapped by Boko Haram. I believe the viewers will care."

*****

No comments:

Post a Comment